There is a moment, right at the end of Night Of Chill Blue, where Martin Phillipps sings, for the third time, "It’s the night of chill blue, And I hope to God you feel this too."

On The Chills’ debut album, Brave Words, he delivers the last line in a low beat, almost politely apologetic manner to the lover the song is written to.

Live, that final chorus could be interpreted in a completely different way, as something of a howling plea by a musician full of passion, ideas and melodies, urgently wanting to be listened to by an often indifferent world, or at the very least the noisy audience in that night’s crowded bar.

Martin Phillipps played more than 1100 live shows — he knew because he documented them all and collected every last scrap of information about them.

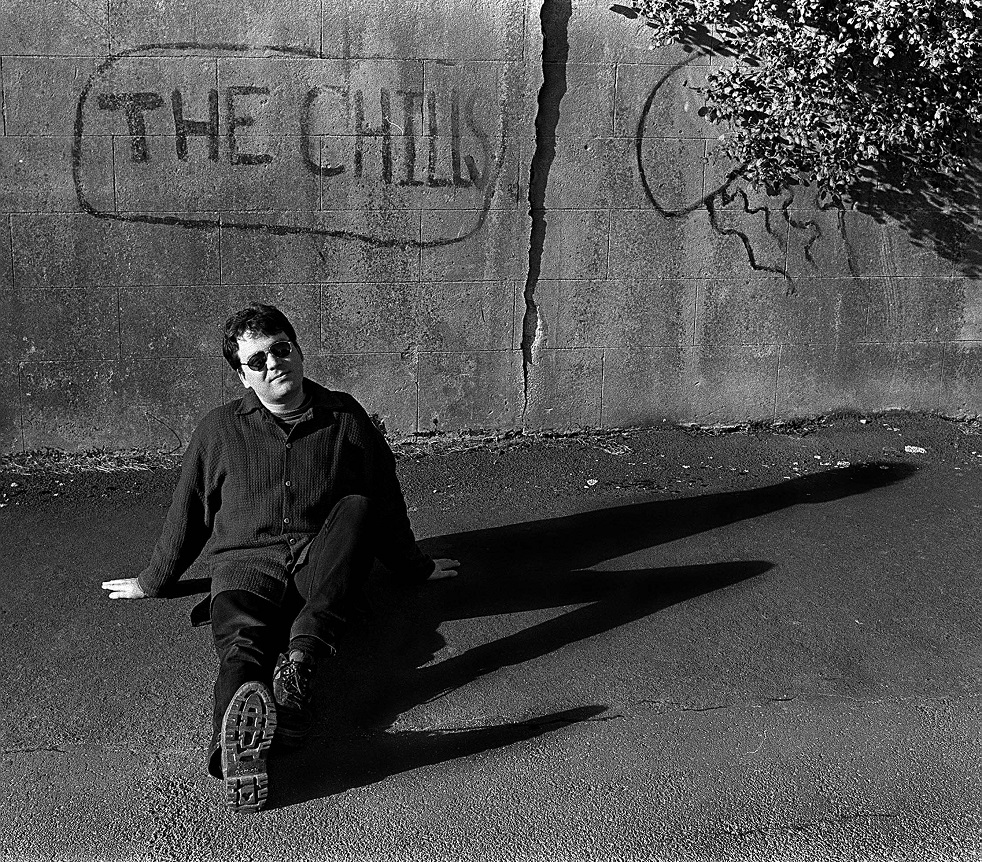

Growing up in Dunedin in the 1980s it would have all seemed rather hard to believe that a globally recognised singer-songwriter could come out of New Zealand’s southernmost city, let alone that it would be the at times painfully shy Martin John James Phillipps — a man who fronted a band which famously went through more than two dozen line-ups and, despite the best efforts of fate to sabotage his career, ended up respected by his peers, loved by his audience and eulogised by the world’s music press.

"It all seems larger than life to me," he sang on Heavenly Pop Hit ... and you wonder quite what Phillipps would have thought about his 61 years being celebrated in a full to overflowing Glenroy Auditorium, in a service compered by a former deputy prime minister, with a national and international audience tuning in through the internet, as it was last Friday.

There would certainly be a song or three to be inspired by such a weird and wonderful journey through his kaleidoscope world. He would also have appreciated the fact that two of The Chills’ records were in the top 10 New Zealand albums that week.

It is a near universal theme of funerals that you hope the dead person being celebrated realised just how much they were valued.

Martin Phillipps had the rare distinction of already knowing that, having enjoyed a late career renaissance thanks to a loyal and dedicated band and manager, and the influence of Julia Parnell and Rob Curry’s documentary film The Chills: The Triumph & Tragedy of Martin Phillipps.

A warts and all account of the band and Phillipps’ health and addiction issues, it screened worldwide and contributed to Phillipps being able to continue to tour internationally, to enraptured audiences. He knew that his all-consuming passion was returned with love.

But there is being a successful musician, living off the shouts of a cheering crowd, and then there is being publicly hailed as one of Dunedin’s leading artists, in the same breath as Hotere, McCahon and Baxter, as Martin Phillipps was last Friday.

Having paid tribute to his personal musical heroes "Wilson, Barrett, Walker, Drake" on Song for Randy Newman Etc, you suspect Phillipps would have been pleased by the crossover.

Phillipps was born in Wellington in 1963, the son of the Rev Donald Phillipps and Barbara Phillipps. The family soon left the capital for several years in Auckland, then for the bucolic delights of Milton, before finally making Dunedin home.

He and sisters Sara and Rachel were all encouraged to learn piano by their musically inclined parents, but it was Martin who really caught the music bug. Being just the right age to be enlivened by the best music of the ’60s and then to be galvanised by the howling snarl of punk rock, 15-year-old Martin Phillipps joined The Same as lead guitarist and then vocalist.

Alternately intimidated and inspired by local punk rock heroes The Enemy/Toy Love, Phillipps met the musically like-minded Kilgour brothers, who he would play with many times in future years.

The Same split and in 1980 Phillipps founded The Chills, a perfect vehicle for his more atmospheric, melodic and dreamy meditations on space, science fiction, TV, films and pop culture. Lineup one featured sister Rachel on keyboards, The Clean’s Peter Gutteridge on guitar, Jane Dodd (from The Same and soon to join The Verlaines, on bass) and Alan Haig on drums. There would be many, many iterations of The Chills over the next 20 years.

The band split a year later and Phillipps played some gigs with Hamish and David Kilgour’s band The Clean, who had just agreed to release a record on enthusiastic Christchurch store owner Roger Shepherd’s new record label, Flying Nun.

The thought of a Dunedin band releasing a record, let alone one as rough and ready as The Clean, seemed entirely far-fetched in the early ’80s, but once they did seemingly every Dunedin band was at it. Despite being told it was all fantasy, Flying Nun made a career in a band seem so real, seem so possible to Phillipps and his peers.

As the EP came out, Haig left to join The Verlaines; The Chills’ new drummer, Martyn Bull, was to play a pivotal part in the band’s history.

By now a trio with bass player Terry Moore, The Chills recorded two singles, Rolling Moon (1982) and Pink Frost, which, in part due to Bull being diagnosed with leukaemia, did not come out until 1984, a year after his death.

Pink Frost is a complete outlier, not just in Phillipps’ compositional history but in New Zealand music itself. A dark, brooding song which sounded as if The Cure’s A Forest had fetched up in the foggy backblocks of the New Zealand bush, it is still a song like no other.

It was a wellspring its writer did not, maybe could not, tap again, but as Phillipps asked What can I do if she’s lost?, Just the thought fills my heart with Pink Frost he struck a chord with listeners everywhere. If you are going to be remembered for just one song, it’s a pretty good one to be remembered for.

Pink Frost hit the top 20 — in those days a comparative rarity for a local single — and follow-up releases Doledrums and The Lost EP also made those dizzy heights. By now word about The Chills had spread internationally and, spurred on by The Lost EP reaching the lower echelons of the UK independent charts, Phillipps and the band toured the UK for the first time.

They came back older, wiser and with a memorable calling card: a video of their adventures in London recording I Love My Leather Jacket, another Phillipps classic and a deeply personal one. "The only concrete link with an absent friend," the eponymous jacket was gifted to Phillipps by Martyn Bull.

It was hung over a coat hook as part of the artwork for The Chills’ best of album; that artwork was re-created on the Glenroy stage, complete with the jacket, as an eloquent backdrop to Phillipps’ funeral service.

By now the world seemed to be Martin Phillipps’ oyster and the band relocated to London to record debut album Brave Words, before touring Europe and North America.

As Phillipps once sang, "It’s good to be an adult but still believe the child in me," as good a one-liner about being a musician as anything anyone has ever come up with. He would wrestle between the dichotomy of the overwhelming confidence he had in the value of his music and the crushing anxiety of facing artistic rejection for most of his career, and bravely face the demons such anxiety spawned.

In 1990 came the validation of The Chills being signed to major US label Warners via its Slash imprint. The resulting album, Submarine Bells, topped the New Zealand charts and the band embarked on a triumphant national tour.

Two years later a new The Chills lineup released the band’s third album, Soft Bomb, but the curse of The Chills struck once more. A band writing thoughtful, melodic explorations of the psyche such as The Male Monster From The Id battled to withstand the flannel-clad tidal wave of grunge.

Once more The Chills split up and Phillipps retreated to Dunedin to deal with the legal and contractual debris of that decision.

But he and music were not done yet, despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles. A new lineup was put together and booked to record in England, but visa issues meant only Phillipps got there.

The resultant album, Sunburnt, was recorded with some gun session musicians, but despite their virtuosity the end product clearly suffered from its troubled gestation.

By this time the dreams may have seemed pointless and the talent cupboard bare for Phillipps.

Back in Dunedin he went through troubled times, attracted unwanted headlines and battled the demons of addiction.

Also some time during this period Phillipps believes he contracted hepatitis C, a savage liver disease which caused him serious health problems for the rest of his life.

It was a challenge he tackled head-on, ultimately becoming a valued advocate in raising awareness of the disease and the fact that with proper treatment it could be managed.

The answer was all around him. A life-long collector and archivist, Phillipps had to hand anything and everything to do with his band — tell him when your first The Chills gig was and Phillipps would open the box for that year and find you the set-list — and the past became his future. Come home, we still need you.

In 2000, after years of hibernation punctuated by all-too occasional live shows, Phillipps released Secret Box, a triple-CD box-set of The Chills ephemera.

The essence of a new The Chills was formed: Todd Knudson (drums), Rodney Haworth (bass) and James Dickson (keyboards, later bass) joined Phillipps and in 2004 Phillipps unexpectedly released his first new music in nine years, an eight-track The Chills EP, Stand By.

More musical reinforcements followed: Haworth departed and Erica Stitchbury on keyboards and violin, and Oli Wilson on keyboards joined, and more music was made. Callum Hampton replaced Dickson on bass in 2019. Phillipps called these new The Chills a perfect collaboration.

Just as importantly, Martin Phillipps was now under new management: Scott Muir was to guide his friend’s career for the rest of his life, freeing him from business and life issues to concentrate on music.

And what music he made. In 2013 Phillipps marked his 50th birthday by releasing a new single, Molten Gold, and two years later Silver Bullets, the first new The Chills album in 19 years, was released.

It was fresh, it was new, but it was recognisably Martin Phillipps. It was also, thanks to his new-found stability, as good as anything he had ever released. Underwater Wasteland was a gorgeous counterpart to Submarine Bells, and Pyramid / When the Poor Can Reach the Moon was both a nod to Phillipps’ life-long obsession with space and a demonstration of his revitalised ambition.

The 2018 release Snow Bound, a rare confection to add to your collection, was Phillipps at his most introspective. He looked back "Yeah, we shared great days, which somehow we fumbled, And then could do nothing but watch as it crumbled," apologised "We made mistakes and we caused heartache, woke up, it was time to atone," and considered his legacy: "I’m not the man you think I am, I’m a complex piece of the plan."

Martin Phillipps and The Chills were riding high again, but few people realised the incredible toll that it was taking on the frontman. That was laid bare in the 2019 documentary, a searingly-honest, access all areas account of the band’s chequered history and Phillipps’ ongoing health issues.

Directors Parnell and Curry opened the film with a sobering visit by Phillipps to his hepatitis nurse, who laid out for him and the audience just how perilous his health was and just how close he was to death.

"I want to leave a much more honest picture of who I am," Phillipps said in the film.

"I do have regrets. I’ve told myself the appropriate lies. You go to great lengths to create a self-serving reality."

The film was widely acclaimed and opened up fresh touring possibilities for Phillipps and The Chills. Each was accepted with delight, and the knowledge that this was another example of the fleeting opportunities the music industry offers, chances which this time were to be grasped with both hands.

The Chills recorded again in 2021 and Scatterbrain, with hindsight, is the sound of a songwriter musing on the end.

"Do the years fly by only when you’re counting," Phillipps asked on the title track, and answered his question on Destiny: "I’m soon to leave and I won’t be seen again, Before I go you need to know I’m autarchic, on the mend."

I won’t cry but there must be some other way of saying goodbye he said, and that will be Springboard: Early Unrecorded Songs, the album Phillipps put the final touches on just before his death on July 28.

"I don’t want to live forever, I want to die alive," Phillipps sings on I Don’t Want To Live Forever, a song off Springboard.