It was the oddest sensation, like someone was rapidly, repeatedly, flicking sounds from one side of a pair of stereo speakers or headphones to the other. I thought I would swoon.

I was standing in the driveway of my old schoolmate Dennis’ house. He was talking to his neighbours and I could hear the blood pumping in my head as their voices lifted and fell in my ears. Then, as suddenly as it started, the sensation stopped.

It was my last full day back in the United Kingdom after three weeks working on some stories and a book.

I’d spent it at Chiswick House in leafy West London, chasing in the footsteps of The Beatles. On Friday May 20, 1966, in the grounds there, they made what is generally regarded as the very first music video, singing their then-new single Paperback Writer and Rain.

That Wednesday I sat on the benches they perched on in the film clip, stood by the Roman statues they sang in front of, and saw the long cedar branches they larked around on.

By the time I got the train and walked the final stretch to Dennis’ house, I’d notched up 18,000 steps for the day, about 12km. It was neither mild nor cold, but I felt slightly too warm as he poured the first of several cups of tea.

I caught an Uber back to my hotel and hunkered down with a mask on in the back seat. By now I was sweating badly and decided to pack my case before going to bed so I was ready to travel the next afternoon if I miraculously recovered.

It was a night without sleep, a crushing headache, awful sore throat and the sheets wet with sweat. It hit me in the small hours: there was no way I could even get myself to Heathrow Airport, about 10km away, let alone fly to the other side of the world. At 5am on Thursday I was on the phone to Emirates delaying my return flight until Monday, though it was difficult to know how long to postpone.

I booked into the Premier Inn Ruislip hotel for another four nights, despite the fact it had no food service and the promises it would fix its defunct free Wi-Fi had now been broken daily for a fortnight. As much as that was annoying and made video-calling the family at home impossible without using truckloads of expensive roaming data, I wasn’t up to looking for better accommodation. I could hardly get out of bed.

I also got in touch with the travel insurance company to extend my cover for another four days, just in case of another misfortune. That sparked a string of emails and phone calls to my mobile from Australia, Poland and Malaysia. Were they scam calls, I wondered at first?

My brain kept spooling back to the jam-packed Jubilee Line train from Baker St to Green Park about 48 hours earlier. As the train stopped at the platform, I couldn’t see how I could squeeze in. My face was in someone else’s armpit, my arms twisted and squashed against the next person’s body.

Then it was another sardine-like Piccadilly Line train from there to Covent Garden, followed by a slow ride in a densely stuffed lift to the surface (this being one of the deepest stations; the 493 stairs up are just for emergencies).

Back in the present, I summoned up some energy and shambled to the chemist to buy a Covid rapid-antigen test. They were high up on the shelves, and didn’t look like best sellers. The pharmacist looked really surprised that anyone would go into the shop with a mask on, let alone buy a test. The sweat ran down my face as I returned to the hotel.

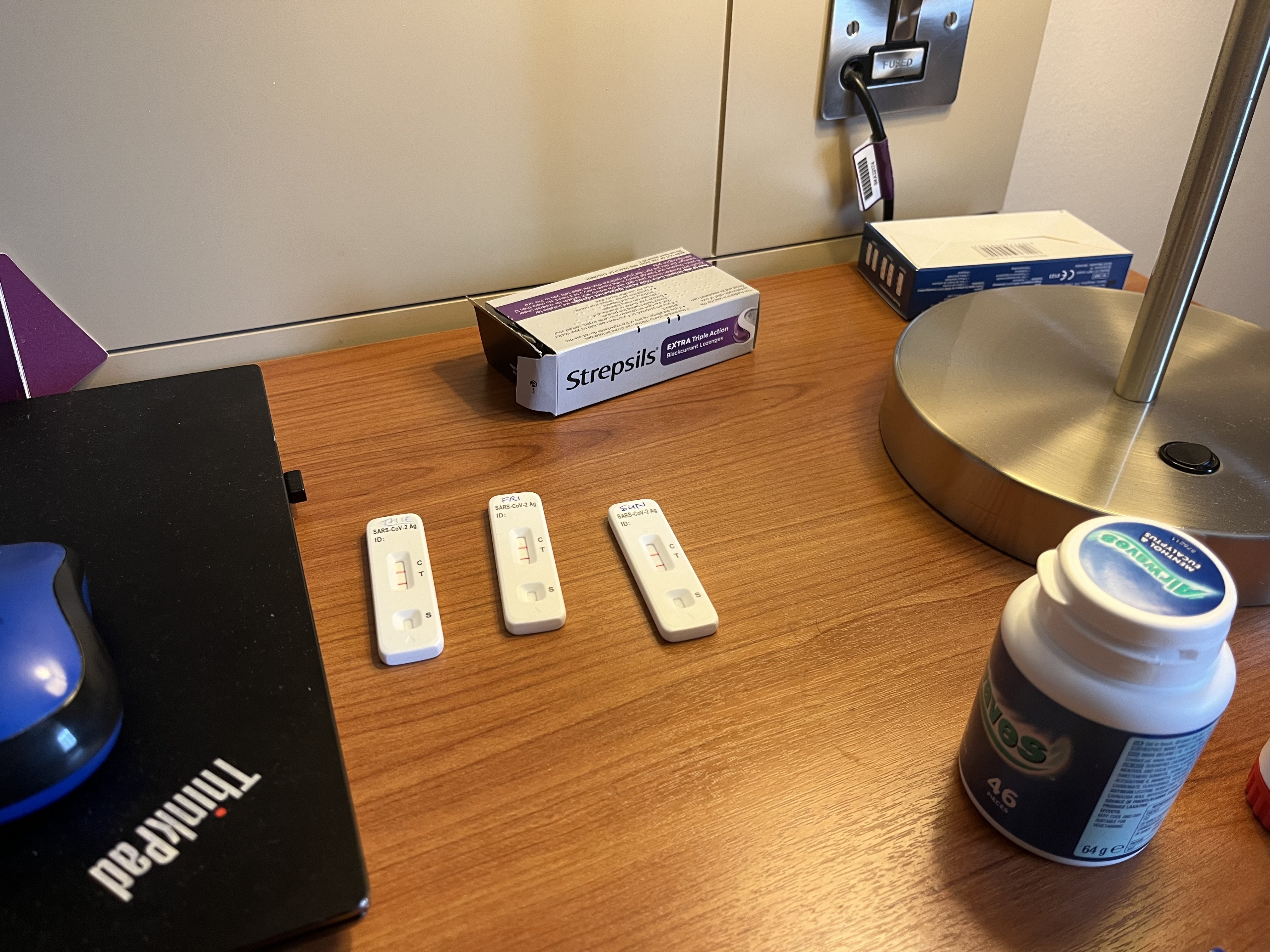

No surprise that within a minute or so there were two lines on the Covid test. I felt vindicated for not travelling. I messaged my family back in Christchurch (it was the middle of the night there) and also my London relations living nearby. That was the last I saw of them.

I woke up from a clammy nap to more calls from the insurers in Malaysia. Before extending my cover, they wanted me to find a doctor in London who would verify my illness. If I couldn’t do that, maybe go to the A&E department at the hospital?

Knowing the parlous state of the National Health Service, there was no way I was going to clog up Hillingdon Hospital’s emergency department for a certificate. I’d be laughed out the door — or sit there for 12 hours emanating the virus and be sent away unseen at the end of the day.

What can you do to help me get the certificate, I heard myself ask the insurance representative. And I thought, why is the onus on me while I’m so sick and can barely make decisions?

After I’d stressed about it, they told me they had a list of private consultants they could use and would arrange an online consultation, at my cost of course, while I did another test for the on-screen GP. That’s more like it, I thought. But I was left with a (non-Covid) sour taste in my mouth over how insurance companies don’t seem to appreciate you might be feeling like death warmed up and not thinking rationally.

On Friday morning I woke congested, coughing and still feverish. I bought three more Covid tests from the now even-more surprised chemist and waited anxiously for details of my online consultation and how much it would cost.

The insurer’s email arrived late in the morning saying it would cost €182, the equivalent of $NZ320, and wanting payment in advance. A few hours later I had a WhatsApp call from an American doctor in Spain.

He told me to test again on Sunday afternoon and see how I’m feeling before deciding whether to fly on Monday evening. A certificate saying I was not fit to travel came through quickly, which I forwarded to the insurers, who said they would be in touch on Sunday to see how I was and discuss progress on extending the policy.

My cover lapsed on Saturday. The next day, feeling a little less clogged up and sweaty, I was now uninsured and miles from home. The insurance company had not explained my position regarding cover while they kept debating whether they would extend the policy or not. Don’t break a leg or die now, I thought.

My third Covid test was still strongly positive. I pushed out the flights to Thursday evening, which cost a fortune, sent the insurers the new itinerary and also a photo of my latest test. Their response was they still couldn’t decide whether to extend my cover until they’d talked to my GP to make sure I didn’t have undeclared pre-existing conditions when I took out the policy.

It wasn’t until Tuesday afternoon that the insurance company finally confirmed my policy had been extended to allow me to get home. Forty-eight hours later I was in the air and never so pleased to see the Canterbury Plains two days after that.

The Covid debacle cost us close to $4500 in changed fares, extra accommodation, medical expenses, food and transport. The insurers sent an electronic claim form which was a challenge to fill in. Twice the details disappeared, and there weren’t enough lines to list individual expenses incurred. There were a few things I didn’t bother to claim for because of that.

The whole process had been way more stressful than it needed to be. I understand insurance companies need to be cautious and check everything out, but there was always this feeling they thought I was lying or they were trying to somehow trip me up.

In the first few days of being sick, with my energy at its lowest and feeling dreadful, it was like being harassed with unreasonable demands when I could barely think straight. Until the doctor gave me the certificate and reassured me I was doing the right thing so as not to infect an aircraft, it felt like that was just what the insurance company thought I should have done.

All I wanted at that time was to extend the cover for a few days, not make a claim, and I wonder if I’d have had the same hassles if I’d told them I needed it extended for work, not health, reasons.

Looking back now, I learnt three lessons:

Don’t rely on a mask to keep you safe on a cramped Underground train.

Keep all your receipts.

And don’t get sick.